The lust for fresh food, it turns out, in many ways is responsible for today’s world food economy. Those railcars full of California lettuce headed to New York in winter? They’ve been traveling that path for nearly 100 years. Feedlots for fattening cattle? They got their start in the late 1800s. All because people wanted the crunch and taste of food that hadn’t been dried or canned.

The lust for fresh food, it turns out, in many ways is responsible for today’s world food economy. Those railcars full of California lettuce headed to New York in winter? They’ve been traveling that path for nearly 100 years. Feedlots for fattening cattle? They got their start in the late 1800s. All because people wanted the crunch and taste of food that hadn’t been dried or canned.

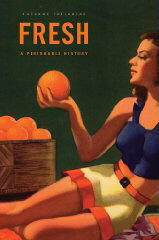

Susanne Freidberg, in her fascinating and meticulously documented book Fresh: A Perishable History (Belknap Press), details these and numerous other examples of the human hunger for fresh food, even the debate over what qualifies as “fresh.” Is aged meat fresh? What about pasteurized milk? Fruit two weeks from the tree? Six-month-old eggs? It all depends on your point of view.

Refrigeration and labor

The advent of refrigeration including the ice trade, which Freidberg documents, created new possibilities for fresh food and promoted the worldwide food distribution system we now have. With refrigeration and transportation advances, fresh food was possible for the masses, not just for the landowner with his or her own fruit trees, greenhouse, dairy herd and chicken coop.

At the same time, however, today’s massive food distribution network relies on the poorly remunerated work of the world’s poorest laborers, just as the rich landowner once depended on servants to harvest and prepare his food. Thus, much agriculture and horticulture to feed us rich (by world standards) Americans and Europeans has been pushed to third-world countries. And those countries sometimes wind up growing cash-crop food for export rather than food they need to eat.

Even as the local-food movement has tried to reverse that trend, the fact that land is expensive near cities, where most people live, means that true local food often is very expensive (to cover the farmers’ high land costs) or not as local as it might be. And the labor of immigrants, often illegals, is almost a necessity to keep our food as cheap as we want it to be, even when the food is local.

Familiar issues

Meanwhile, many of the food issues we discuss today are as old as the feedlot. Freidberg quotes from M.J. Rosenau’s 1912 book, The Milk Question, with this familiar observation: “When the producer and consumer were near neighbors…the one had a personal interest in the product he furnished the other….the separation between the two has [now] lulled the conscience of the producer.” Hence, we’re more secure in buying ground beef from our local vendor at the farmers market than a frozen beef patty from the supermarket that could well have come from one of the companies involved in large-scale recalls. (Read the latest recalls at the U.S. Food Safety and Inspection Service.)

What about nutrition? Freidberg tells of the American Medical Association’s endorsement of canned vegetables’ being as nutritious as fresh, which we now know is not true. And taste? It’s tricky. Sometimes gorgeous fruit tastes like nothing, and flash-frozen fish may taste better than freshly killed fish that have suffered innumerable stresses as they get shipped thousands of miles to swim in retail vats in Hong Kong.

Freidberg writes, “We’ve all come to see freshness as a quality that exists independent of all the history, technology, and human handling that deliver it to our plates.” In her fine book, she explains that history and just how complex our food system is. By focusing on meat, eggs, milk, fruit, vegetables and fish she shows us that today’s food is based on “interdependencies and inequalities, forged through trade, conquest and politics… [and] sharp contradictions between marketed ideals and industrial realities.”

Much to ponder

Even as some of us beat a path to the farmers market or CSA, the history she describes affects the selections available and their path to our refrigerator. She gives us much to ponder and presents it in a highly readable volume largely devoid of value judgments. I learned a lot. Give it a read. It will indeed give you a fresh look at your food.

Fresh: A Perishable History

By Susanne Freidberg

Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press, 2009

No Comments so far ↓

Like gas stations in rural Texas after 10 pm, comments are closed.